“Nobody ever got fired for buying IBM.” — 1980s

If you’ve heard this saying about buying IBM, have you considered what it means? It’s not really about IBM; it’s about the safety of the herd. What made IBM such a safe choice was its ubiquity. It’s hard to blame someone for making the same choice as everyone else. Buying your mainframe from another vendor was risking your career. If the project failed for any reason, it was easy to blame the choice to not go with IBM as an unsafe risk that didn’t pay off.

“Nobody ever got fired for using agile.” — 2020s

Luckily for us, we’ve entered a similar period of ubiquity for agile software development. For the last twenty years the risk takers have done the hard work to create a safe, default choice for everyone creating software. The herd is now using agile. Our projects may still fail, but no one’s going to blame our choice to use agile as the cause. Should we go with the herd? We do want to avoid unnecessary risk, but not at the cost of making good choices for our projects. A “safe” choice can be risky if it’s not a good fit. Buying IBM wasn’t always the best option, and there are contexts where agile isn’t the best software development choice. You should understand when lean software development can provide a decisive advantage over agile.

If you haven’t read part 1 of this blog series, you may hear “lean” and be thinking about lean startups or lean product development. You should read part 1 to understand how lean software development differs from these other uses of “lean.”

Before considering the choice between lean software development and agile, it’s helpful to understand the challenges of waterfall methods that led to the creation of both agile and lean. From there, we can best understand the common origin of agile and lean, and how they differ.

What’s waterfall software development?

Waterfall is a descriptive name, given after the fact, to a whole family of software development methodologies derived from other engineering fields, namely construction, durable goods, hardware engineering, and so on. Waterfall methods break down project activities into a linear sequence. Each activity depends on the output of the prior activity and progress flows in largely one direction (downwards like a waterfall).

This happens at the macro level, as in the above diagram, but also at the micro level in detailed PERT or Gantt charts. Waterfall methods focus on using detailed planning to manage the risk of budget and timeline overruns.

Waterfall methods are based on the idea that if something goes wrong it’s because of a planning deficiency. The specification wasn’t specific enough, the design wasn’t detailed enough, or the estimation wasn’t granular enough. In a waterfall method, more detailed plans equate to less risk.

So what’s wrong with waterfall?

Waterfall methods are a reasonable way to plan the upcoming hour or day, but these methods aren’t focused on such small timeframes. Waterfall has a built-in impetus that encourages the growth of the planning timeline. No one feels OK spending four hours of their work day planning the other four hours of work. Nor can we fathom spending four days to plan the implementation activities of a single day. The only way to amortize the time and effort spent on ever more detailed planning is to plan ever longer and bigger projects. Unfortunately, we’ve learned that as the size and timeline of a plan grows, the risk grows exponentially.

There are two fatal flaws inherent in waterfall development that create this risk, and depending on which flaw you focus on, you arrive at a different alternative to waterfall. One of these flaws is best addressed by agile, and the other flaw by lean software development.

The first fatal flaw of waterfall is a hubris about what we know. We now realize that developing software is a knowledge-creating process. Waterfall assumes we already know everything that’s important to developing the system, and we can capture this knowledge in the form of requirements. These requirements inform a design, which we can then build, test, and ship.

When we examine failed waterfall software projects, we usually find the source of the failure was everything the team didn’t know upfront. It doesn’t matter how detailed and rigorous the plan is if the plan is simply wrong. In fact, the more rigorous an incorrect plan, the worse it is, since we invested more time creating it and are less likely to tolerate big changes.

Waterfall isn’t a process that accounts for uncertainty; it attempts to maximize learning to dissolve that uncertainty. But when we create software, we usually lack complete knowledge about the problem we’re solving, the context we’re solving it in, the constraints of the business and the technology, and the real needs of the various users. What we know is both flawed and limited. Plenty of what we think we know turns out to be wrong, and there are plenty of things we don’t yet know we don’t know. Agile software development focuses on addressing this first fatal flaw of waterfall: incomplete knowledge.

What’s agile software development?

Agile software development attempts to unlock the team from rigid plans and instead embraces project-long learning.

The activities we do in waterfall methods — planning, requirements, design, implementation, validation — are still necessary. They don’t go away in agile, but the timeframe for these activities radically shrinks, and some steps collapse. Detailed requirements shrink to become sprint planning. The quality assurance step merges into development. We insert an important feedback step with external feedback from the customer using working software, and we add internal feedback from the team in a retrospective. Then the whole process becomes an iterative circle that’s repeated every sprint, usually two weeks.

What does this shrinking and reflective iteration of the software development activities accomplish? It reduces the risk that you waste time building the wrong thing.

Teams don’t get smarter when they decide to use agile. Teams gain knowledge through the act of building software. The key to agile development is that the plan for what to build and how to build it isn’t created at the start of the project when the team has the least amount of knowledge. Each iteration of the agile process benefits from everything the team learned in prior iterations.

Great agile teams optimize their iterations for learning; they aggressively attack their risks and knowledge gaps, bravely choosing to build these parts of the product first, trading short-term discomfort for long-term risk management and success.

Learning isn’t free. It won’t happen without a source of corrective feedback, and time and space to synthesize and gel. Agile teams have a customer (or close surrogate to the customer) “in the room” to provide rapid feedback and course correction, and they set aside time during each iteration to reflect on new information available to the team, on newly-identified risks and knowledge gaps, and on how the team’s performing. Team-wide learning occurs through this process of deliberate knowledge consolidation, which then informs future iterations.

The ceremony used by many agile teams has grown considerably, but as long as software’s built in short, knowledge-creating iterations that are focused on the biggest risks, then none of these practices are specifically required to be agile. Agile teams will vary, but some common practices are:

- Product backlogs

- Sprint planning

- Sprint retrospectives

- User stories

- Story points

- Burndown charts

- Scrum

- Extreme programming / pairing

So agile helps us manage the risk that we spend lots of time building the wrong thing. But what about cases where that risk is low? Sometimes we do have verified knowledge about what we need to build. Some examples of this (admittedly more rare) context are with mature products with proven product-market fit, or technology modernization replacements of existing systems. Can waterfall be a good approach in these cases?

So again, what’s wrong with waterfall?

Waterfall is still not a good answer, even when the risk of building the wrong thing is low. The more complete the knowledge you have about what you need to build, the more likely the second fatal flaw of waterfall development will come into play. The second fatal flaw of waterfall is that it doesn’t account for the cost of undelivered value. Waterfall doesn’t optimize for timely, incremental value delivery.

The software we’re in the process of building, and all the software we’ve built that isn’t yet in use by users, is analogous to our inventory. We know from manufacturing and retail that excess inventory should be avoided. It’s expensive! We spent money developing this software, but it hasn’t created any value for our users, and with the waterfall method it’ll be a long time before it does.

To justify the huge investment in detailed requirements gathering and enumeration, detailed product and technical design, and detailed project planning, the typical waterfall project is between 6 and 24 months long. Projects longer than that aren’t uncommon. That’s a long time to accrue valuable inventory with no return. Lean software development attempts to address this second fatal flaw of waterfall: delayed value delivery.

What’s lean software development?

Lean software development attempts to reduce costs and speed up time to value by eliminating waste in the software development process.

As was described in part 1, lean software development is directly inspired by lean manufacturing. As a lean manufacturer, you know what you’re producing — for instance, a car, or a mobile phone, or a desk chair — but how will you improve as a manufacturer? By making more with less! More items produced, in less time, with less wasted product, less people, less inventory, and ultimately less investment required to capture more revenue.

Let’s pause here briefly and compare lean manufacturing with agile software development. The key risk to be managed by agile is the risk of making the wrong thing. With lean manufacturing, the key risk to manage is the risk of not being as profitable as possible. When we apply the principles of lean manufacturing to software development, we do so to manage the risk of not delivering value quickly.

A focus on delivering value more quickly means you need to be precise about what a customer values. You need to know which activities in the development process create that value and which parts of the process don’t. Any activity that doesn’t create customer value is waste and can be improved or eliminated.

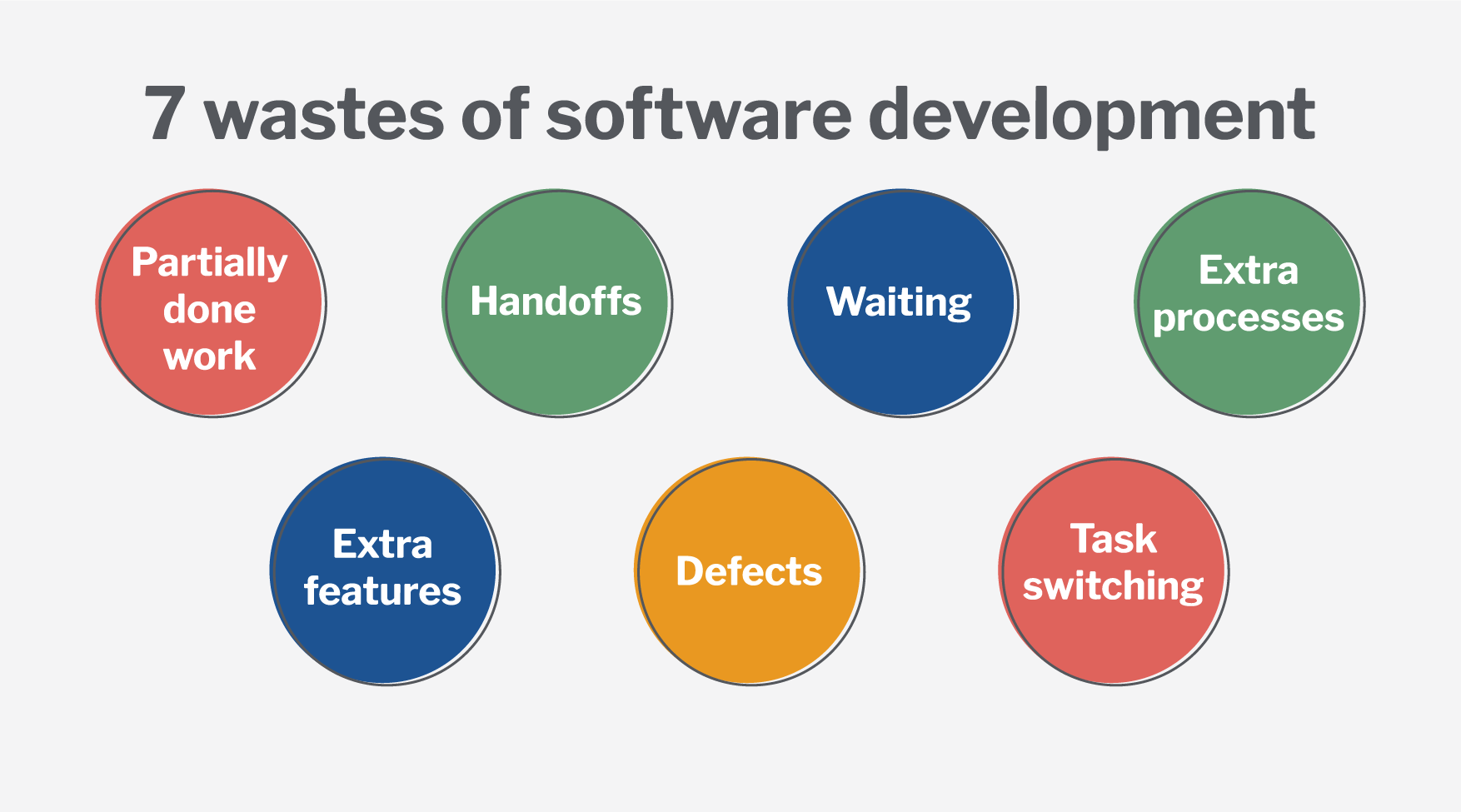

Lean software development practitioners have identified the seven most common types of waste that occur in software development.

Why is limiting work in progress so important to the economics of creating software? Let’s use a simplified example. Suppose we have four new software capabilities our team needs to deliver to eager users. How should we think about delivering it? What are our options? In the video below, we explain why lean software development focuses on limiting work in progress:

In my experience, work in progress is often the largest source of waste, but each team is going to create waste in these seven areas in different amounts and in different ways. Lean software teams are focused on continual improvement to eliminate waste, however and wherever it occurs. This focus on waste reduction and elimination isn’t a principal focus of most agile software teams.

Other lean software development principles

Now that we’ve covered one primary principle of lean software development — eliminating waste — let’s consider some of the other principles:

- Build quality in

- Create knowledge

- Defer commitment

- Deliver fast

- Respect people (not processes)

- Optimize for the output of the whole system

As we cover each of these principles, consider how close or far the principle is from the development process you’re most familiar with, such as agile. Is the principle compatible or incompatible with what you’re doing today? Is it something you’d normally focus on?

Each of these lean software development principles is a response to conventional wisdom of the time, the early 2000’s, and to waterfall development, so I’ll present that conventional wisdom as a myth that needs refutation. Entire book chapters have been written on eliminating these seven forms of waste, and we don’t have room in this article to cover all seven of them, but I’d like to discuss two of them: extra features and partially done work.

The single biggest source of waste is extra features. Nothing could be more wasteful since everything we do to create an unneeded feature, even those activities that are normally valuable, is simply wasted.

Eliminating extra features is the biggest overlap between lean software development and agile, and it’s why they both require strong product management and deep knowledge of the problem space. Eliminating this type of waste isn’t easy, but it’s less challenging for lean software development teams since they’re working to deliver proven value on well-understood problems. Teams without well-understood problems and proven value to deliver shouldn’t be using lean software development.

Another large source of software development waste is partially done work. The strongest signal that a team is successfully adopting elements of lean software development is that they’re focusing on reducing, and then limiting, the amount of work in progress that’s not yet in production. When creating software, work in progress is any code we’ve written that isn’t yet in the hands of the users of the software and providing value to them. This is our inventory, and inventory is expensive.

Build quality in

Myth: We test to find defects.

For lean software development teams, quality assurance isn’t a process that happens after software is built, quality is built into the software as it’s created. This means that testing happens as development happens through some combination of test-driven development and continuous integration. It also means that teams write less code, create less features, and overall have the software do less as a critical means to have fewer defects and higher quality.

Lean software development teams are also allergic to queues of work. Defect tracking systems are queues. They’re collection points for wasteful activity, collecting and documenting defects that aren’t important enough to fix. Lean software development teams don’t collect defects, they fix them. If it’s not important enough to fix immediately, it’s not important enough to spend time collecting it.

The final part of the principle of building in quality is about how lean software development teams think about defects. A defect is the result of the software development system, not a person. It was the process that created the defect, not the developer. Lean development teams “stop the line.” They halt the software development process and ask, “How did the system allow this defect to happen?” Then they fix the system. This is key to continuous improvement. Each defect found is an opportunity, a demand even, to improve how the team is operating.

Create knowledge

Myth: The key to predictable project outcomes is rigorous specification in requirements, design, and planning.

Software development is a knowledge creation process. Knowledge doesn’t get created first, and then software is built. Instead, the act of building software creates knowledge about the problem, and about the best way to solve it.

This can lead to some counterintuitive assessments of how a project is going. Traditionally we consider projects to be “bad projects” if they have a lot of changes from initial expectations of what the software was going to do, how the problem was going to be solved, and even what problems are important to solve. But in fact, these projects are actually good. They show evidence of knowledge creation and learning by the team.

Traditionally, we think of projects as “good projects” if they proceed exactly how they were predicted to and solve the expected problem in the expected way. But many of these so-called “good projects” might not be so great. They can indicate that teams are insufficiently engaged in learning about what users really value.

Lean software development teams are committed to learning from real users using their real software, not from educated guesses about what software capabilities are needed. This commits teams to a few key activities: release early, release small and atomically, release often, and release continually. Lean software development teams commit to continuous delivery and to getting software into the hands of users above all else. Do you think agile is quick to deliver? Lean teams deliver new software capabilities from conception to production on the same day!

All the knowledge creation that occurs when creating software isn’t maximized unless it’s shared widely. This knowledge isn’t forgotten. Lean software development teams value the knowledge they create so they write it down.

Defer commitment

Myth: The act of planning represents a commitment to the plan.

Lean software development teams do make plans, since planning is itself a source of learning. But lean teams recognize that planning doesn’t represent a time or scope or solution commitment.

Planning isn’t just about time or commitments. Planning helps refine requirements, scope, and design as well. Even the problem to be solved becomes clearer via planning. So planning is important, but if all you have is a plan, you don’t have any validated learning. You still have very little knowledge about the software. Commitments made when all you have is a plan aren’t just likely to be wrong, they’re dangerous. The pressure to fulfill the commitment leads teams to ignore key insights and learnings that are generated as a result of creating the software. Therefore, commitments should be deferred until you have the most information possible.

Commitments don’t just apply to timelines, but also to other product decisions. Lean development teams recognize that the way to tackle tough problems isn’t by “making the hard decision” in a time of maximum uncertainty, it’s by deferring tough decisions while attacking them directly via multiple experiments, delivered fast. In this way, lean teams generate new knowledge about which is the right decision and can make the decision when they have the most information. There’s a very critical distinction here: This process isn’t the same as deferring making a hard decision until more information can be collected. Instead, it’s actively creating the exact information that’s needed to make the hard decision into an easy one.

Deliver fast

Myth: Moving too fast is reckless.

Everyone wants to complete projects faster…up to a point, and then people start to get uncomfortable. This is too fast. This is reckless!

Let’s test your own instincts here. If I propose a waterfall development process that would work on a software release for a year, and then ship it, hopefully your warning alarms would be ringing loudly. If instead, I propose a two-week sprint, and that you ship whatever is built at the end of the two weeks, you might feel this to be aggressive (since most agile teams don’t ship every sprint), but maybe you think this is a healthy push that can enable your team to go faster. Now, what if I suggest you develop for just one day, and deploy that into production? How about you ship before lunch? And how about deploying whatever you can complete in an hour?

Here again, your alarm bells are probably ringing. This is too far, too fast…too risky! But in fact, great lean software development teams regularly conceive of software changes and deploy them to production in hours.

How can you be sure of anything in an hour? That’s not a lot of time to think things through or to verify them. What if it’s wrong? Well…if it’s wrong, you’ve only lost an hour, not a morning, or a day, or two weeks, or a year. If it’s wrong, you’ve risked less, not more.

Of course, a lot of things need to be true before shipping software in an hour is the least risky thing you can do. You likely need some substantial improvements to your peer programming practices, test automation, and DevOps processes before you can deliver software from a white board into production in hours. It’s true you won’t get there overnight, but you won’t ever get there if it’s not your goal. You shouldn’t be content waiting two weeks to get software. A lot can change in two weeks, and two weeks is a big investment of time and cost. Lean development teams move faster, delivering more value sooner, with less investment and risk.

Respect people (not processes)

Myth: People follow the process.

A key principle of lean software development is that people should be actively engaged and thinking critically at all times. Nothing encourages people to go on auto-pilot more than following a defined process they’re told is good. An important shortcoming of agile today, and of waterfall before it, was people blindly following a process and expecting it to produce the correct results.

Lean software development intentionally defines principles and areas of focus, but not the processes, activities, and ceremonies to achieve these. Each team implementing lean software development needs to think critically about which areas of waste and principles they should focus on, and how to best implement processes for themselves. A self-defined process requires more active engagement than picking processes off-the-shelf because that’s what everyone else is doing.

An important benefit of teams defining their own activities is they recognize that they’re the inventors of the process they’re following — it’s not received wisdom from gurus. This self-authorship encourages thinking critically about what’s not working well and embracing continuous improvement. Many agile teams pay lip service to retrospectives and continuous improvement, but also don’t feel like they have much flexibility to veer away from agile orthodoxy.

Choosing to follow lean software development principles may be a higher-level decision made for the team, but since each team is required to define their own implementation it requires top-down respect for the people making up the team. The team members also need to respect the experience and judgment of their peers who are defining and iterating on the process with them.

Optimize for the output of the whole system

Myth: If everyone is operating efficiently, then the project is operating efficiently.

I saved this principle for last, because it’s counterintuitive and the hardest to implement. It seems obvious that if everyone is working as hard and efficiently as possible on a software release, then we can’t do any better. But in fact, we can do much better. It just requires a substantial shift in mindset.

Everyone operating efficiently isn’t a goal. If you choose to adopt lean software development, it’s because you want to ship value into production more quickly, and that’s the goal. To speed up value creation, you need to know where the value comes from, which requires a map of the value stream. The value stream starts with a customer and ends with a customer. Everything in between is how value is created and put into production. That value stream is what needs to be optimized, not any individual’s activities. Look for queues, hand-offs, loop-backs, churn, and bottlenecks in the value stream. Ruthlessly remove them where you can and optimize for them when you can’t.

Optimizing the value stream is going to require changes to how people work, and a lot of the push back on these changes is going to come from negative impacts to the local measurements currently being used to gauge the efficiency of people. Adopting lean software development means you stop using local measurements. Many people may need to reduce their own personal efficiency, as measured locally, to optimize the output of the whole system. That’s not going to feel OK…but it is.

When the value stream is mapped and the worst inefficiencies are identified, you’ll notice a pattern. The inefficiencies will cluster around boundary crossings. Hand-offs between companies, departments, teams, systems, and individuals. These are where most delays happen, queues form, and work moves backwards in the stream for re-work. To be able to deliver software into production in just a few days, or a few hours, activities need to be re-imagined and reworked to optimize or eliminate these hand-offs.

Agile or lean — which to use?

Now that you have a better sense of lean software development you’re probably still wondering if it’s better for your own projects. Agile and lean are siblings; both were born out of a rejection of waterfall, but they aren’t identical twins. They share some of the same principles and practices, so there’s a strong family resemblance, but they aren’t simply two names for the same thing. This short table summarizes some of the key differences between agile and lean software development that we’ve discussed.

When choosing which approach to apply, I urge you to focus on the key strength of agile and the key strength of lean, so you can choose the approach that best maps to the context of your project. The following chart can help you understand where your project fits.

While the real world often isn’t as clear cut as this chart depicts, finding where your own projects fit on this chart is helpful. Projects that face great uncertainty but fewer expectations about the amount of software to be delivered, often just an MVP, benefit most from agile. Projects most suitable to lean software development have a strong business imperative for delivering software into production but fewer questions about how to best solve the problem — a legacy modernization project is but one example.

Moving forward

Since agile is now the default choice for how to develop software, you need to be confident of your reasons before going in a different direction. You can expect some push back. Not practicing agile is like not buying an IBM mainframe — it seems risky. All the same, if you’re confident about the context your team is working in and those circumstances favor lean software development, you should boldly apply the principles of lean software development that make sense for your team.

If you think some of your projects could benefit from lean software development, you’ll want to read the final article in this blog series for practical advice on applying lean software development principles. That article, as well as the section of this article on lean software development principles, is largely distilled from Mary and Tom Poppendieck’s excellent book on lean software development. If you’re already convinced your team can benefit from some of these practices and focus areas, I recommend you read further.